The happiest moment of my life occurred on the day I held in my hands the golden ticket, the winning lottery, the thing I desired most in the world—a visa to America. Since then, life has gifted me many remarkable moments, but none have been as electrifying.

I was a 14-year-old Iranian girl, standing with my parents in a crowded and humid auditorium in India, staring at the red shimmery stamp on my passport. My entire body hummed with the anticipation of escaping the place I called home. There was the war, of course, and crackdowns on dissidents, but more than anything, I longed to dance without the fear of getting arrested.

The Iran-Iraq War had begun seven years earlier on a brisk autumn day in September of 1980. I heard the adults quote Rumi as I made a pile of yellow and orange leaves in our yard. “I accept, I am the prisoner of this world, but tell me, whose belongings have I stolen?” Life had taken on a chilling unreality since the Islamic revolution erupted months before. The new strange laws banned girls from running in public, leaving the house without hijab, or playing with boys. Spies lurked and listened to private conversations. Protesters were tear gassed and imprisoned, and anti-revolutionaries were executed. Then bombs began falling.

There was a real war. And then there was the war on joy. Our collective spirit wilted as the arts were targeted and most music became illegal. The assault on our coping mechanisms took a toll. In the darkest of moments, poetry became our lifeline as ancient poems were immune to this brutality. The irony never escaped us that while we could still recite Hafez and Khayyam verses celebrating the Beloved with songs, dancing, and wine, we couldn’t partake of alcohol. We couldn’t dance. We couldn’t sing.

As the years went by and funerals became part of our daily lives, we grew restless. We broke the law. Boys and girls met in secret. Friends of our family made homemade wine with Shiraz grapes. I danced in my basement to contraband music. Our neighbor threw a birthday party for her daughter. The gathering that hosted boys and girls dancing was raided by the Morality Police who pointed AK47s at us. We survived that night but at one point in the school year, half of my sister’s senior class was arrested and detained. One was executed.

Each year I grew more depressed and more daring in equal measures. I wore my hijab and went to school, playing the detested role of the obedient, subservient girl. At night, I became alive, dancing in my room. When the unquenching rage stole my sleep, I sneaked out to write anti-regime graffiti on walls. My parents began to worry.

It’s not an exaggeration to say a poem may have saved my life. As the war raged, no country welcomed Iranian refugees. Iran had become an unofficially “banned nation.” My mother, a poet, had an idea. We would apply for a U.S. visa in India, but first, we had to get a visa to India. She submitted a poem about India’s Independence Day along with our visa application. The Indian ambassador must have liked the poem as he granted us a visa to India, where I experienced the happiest moment of my life: holding my visa to America. But perhaps happy moments have their own set of fine print, as the price of leaving the house without fear turned out to be isolation and homesickness. I made it to the U.S. but my parents had to return home.

For months in Las Cruces, New Mexico, I looked for pieces of my loved ones wherever I could. I desperately sought their voices and manners in the people walking in and out of my new life. I saw my uncle’s hunched shoulders, standing in the supermarket line. I heard my sister’s deep-throated laughter in my biology teacher. I missed them to the point that out of nowhere, the world would spin around me. Clinging to the hallway wall of my new school, I would will myself to the bathroom, where I tried to wrestle my breath from the clutches of longing. When I arrived home, I binge-watched MTV and danced. I didn’t stop until I felt Rumi’s poem in every cell of my being:

Dance when bloodied and battered,

you enter the temple of Love

Dance when your very heartbeat is

that of the Beloved

Dance when you’re broken open

Dance when you’re free

—Rumi translated by the author

Long after my ears shrank back to their normal size and stopped listening for the next disaster, and my eyes stopped darting about for spies, I began holding dance sessions for refugees in San Diego. I wanted to give them what was denied to me as a child and what I longed for as a newcomer—music and a sense of community.

Like me, for these newcomers, the thought of home welled up saudade, a yearning for a place that was no longer there. We didn’t have a person in our mix who hadn’t lost people to war or violence. There wasn’t a soul who didn’t consider themselves fortunate for escaping. Yet, there were the shards of pain from a broken homeland, a broken life.

The first notes of a familiar song seemed to open a portal to the glorious sanctuary deep inside each of us, where all was beautiful, where all was well. As Iraqis sang and danced to Iraqi love songs, everyone joined in, rejoicing in their delight. When we played a popular Syrian song, we screamed along with our Syrian friends and clapped and shimmied. We drummed to Afghan ballads until we dissolved in the beat.

I am the beat and the rhythm

of this moving world

And rhythm of this world is me

Among lovers, even love screams my name

When it becomes drunk and playful

Love can’t help but spill my secrets

I am the rhythm of this moving world

The heartbeat of life

Bits of universe collide in their joy

and unveil my faceless face

I am the water flowing in the river

and the wine in the glass

Beware! This wine is here to shatter the glass

I am not meant to live small

For me to be, you have to disappear

—Rumi translated by the author

Around 2018, a crisis began brewing at the U.S.-Mexico border. Desperate asylum seekers from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and parts of Mexico escaped violence and death only to be confronted by border guards who turned them away or arrested them, took their children away, and detained them in horrid detention centers. I interviewed enough asylum-seeking parents to realize that fear and suffering were their constant companions. Going back wasn’t an option for most and many waited in migrant shelters to be processed by the U.S. immigration authorities. As days of waiting turned to weeks and months, we began dancing together, blasting popular cumbia songs my new friends had grown up with and loved. A baby always napped to our ruckus. Kids lit up as they struck the drums. We held sessions in rain puddles and through measles and mumps outbreaks, and fires. Bloodied and battered, we danced in the temple of Love.

The asylum seekers stuck in Mexico told me they need joy and hope to survive. When the pandemic began, they asked if we could continue dancing through Zoom. And we did. And we do.

Dancing alone in my living room reminds me of whirling in my basement in Iran. As we prepare to welcome Afghan refugees, I remember how terrible it was when music was outlawed. I’m still the 14-year-old girl who longs to dance with others as the world falls apart around them.

When I settle into the discomfort of “how long” and “what then,” I notice throughout the years, the metaphor of dance has become a Serenity Prayer, a zikr of sorts for me. It beckons me to pivot and flow with what I cannot control. It reminds me to bring all of me to which I must change, not leaving anything small or trivial behind. And it points me to the stillness from which music arises.

*

This essay originally appeared on Powell’s Book blog on September 21, 2021.

![]()

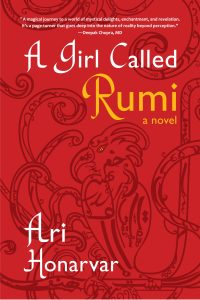

Ari’s novel A Girl Called Rumi is published by Forrest Avenue Press and available here.

Ari’s novel A Girl Called Rumi is published by Forrest Avenue Press and available here.

Learn more about Ari on our Contributors’ Page.

(Photo: DFID/flickr.com/ CC BY-SA 2.0)

- We Couldn’t Sing, We Couldn’t Dance by Ari Honarvar - December 30, 2021