I remember my father going to the chicken pen to select the birds that were going to die. Sometimes Dad did his chicken-snatching in broad daylight, netting fleeing birds or making a swift grab for their legs. An easier way was to visit the coop after dark, a chicken angel of death choosing the doomed from their roosts as they blinked at the beam of the flashlight crashing in on their sleep.

The chickens did not go quietly into that good night. As Dad held them upside down by the legs, they squawked and flew desperately in place, wings beating his arms as he leaned away from the turbulence. Gradually, the chickens would tire, or else realize flying in place wasn’t doing them any good.

Dad stowed each victim, or as we preferred to think of it, future chicken soup, in a plastic crate, where it would hunker tight against the other chickens doomed to the chopping block. Their frantic squawks gave way to silence or to an intermittent, resigned cluck, like the single peep young chicks make—but older, raspier and sadder.

Their destination was a bulky chunk of cedar wood, a chopping block whose surface was pitted and stained from past butcherings.

Each chicken’s turn came when Dad pulled it out of the crate, again grasped its legs firmly, and placed its neck on the block.

Even as youngsters, we knew this was the big moment. It passed quickly: The raised ax, the swift chop. The chicken’s body came away and went flapping and hopping around the yard, the nerves jangling with no brain to modulate them anymore. We were agog that an animal could be dead and still move around sans head.

Ah yes, that laid back rural life you’ve heard about, moving to a slower beat without all the messiness of urban existence.

Butchering time was when I began to appreciate some of the mystery of death: that one second this animal would be breathing and blinking, and moments later, its head would be lifeless on the chopping block.

The chickens were then cut down into their component wings and breast meat and legs and taken inside, where my mother washed them and wrapped them in freezer paper. The next time I would see the chicken was on my plate, transformed into the meal so recognizable to millions of people who have rarely seen a live chicken and have never seen one die.

When I got older, it was me wielding the ax, and it became a much more somber affair. I was the one making the decision on which chicken to pluck from its pen where, presumably, it had been contentedly dust bathing or catching crickets or eating young greenery, never suspecting the end was near. Were they ever depressed and tired of life? Not in my imagination. When I snatched them away, I assumed it was from a life of contentment. I was a stalking grim reaper of chickens.

I suspect many others who grew up killing animals, an experience much more common a few generations ago than it is today, did it with less sentimentality. Perhaps, less guilty and morbid than me, they could without a qualm help the animal along its natural metamorphosis from fluffy chick into a chicken pot pie.

Or, maybe, like me, they felt some distress and were just quiet about it.

The unease never completely went away. But I had to shove that down and move on. This was how the world was, and this was how we got meat.

My family was Mennonite, a faith tradition that frowns on violence, believing we are called to love our enemies and eschew war, even if that comes at a high personal cost. You can’t love your enemies and kill them, the reasoning goes.

Most Mennonites will kill an animal, though. (Animals aren’t enemies, after all, if you want to get technical.) More importantly, they’re not human. We were taught to be kind to animals when they were alive and to kill them cleanly and humanely.

My family believed in heaven, but chickens fell into an awkward category. We were inclined to agree with atheists that they had no immortal souls, that the chicken ended there on the chopping block and simply was no more. Dogs, closer to us and more part of the family, we hoped might have souls so we could have a joyous reunion someday in the afterlife. A reunion with the chickens would be truly awkward.

We did not, of course, eat our dogs or cats. What kind of monster would do that?

When it came to the animals in the killing category, wild creatures were much more challenging to pursue, not being dumb as chickens and stuck in a coop, and therefore more exciting. My father was a hunter, and we kids waited eagerly for him to come driving in the lane after dark to see if he had a deer in the back of the truck. We’d go running out the door to hop up in the pickup bed, fascinated by the buck sprawled out there, stroking its rough brown hair, running our hands down its smooth, hard antlers, touching its cold black nose. We could never have come this close to the wild creature if my father hadn’t killed it.

I thought deer were beautiful and was fascinated by them, and it was my ambition to someday kill one, too.

The first time I killed a deer, a young buck with barely more than spike antlers, the impact of killing didn’t hit me as hard because of the way it happened. My father helped me track it after dark, until finally we saw it lying up ahead in the flashlight beam.

“Hey, look at that!” he said proudly. I was over the moon.

Our finding of the dead animal was separated from the killing shot by hours, the sadness drowned out in the flood of excitement at getting my first deer.

It bothered me more later. Subsequent deer died where I could see them, dropping from my shot and flopping on the ground, reminiscent of those chickens, until gradually they grew still.

Hunting is such a complex and strange flood of emotions, far more powerful than the killing of a chicken. There’s the heart pounding moment when your hunt hangs in the balance—all those hours of looking for tracks and calculating the best spot for an ambush and the many hours of waiting, all coming down to this climax. Will you be equal to the challenge, or will you waste the chance?

Later, melancholy mixes with excitement as you think about the life that is no more, the end of an animal you respect so much. Satisfaction, pride, a pang of regret and sadness at being the one who inflicted this violence. Joy in a successful hunt, the payoff for all that time spent finding the animals, then sitting quietly or stalking while reading the sign and the wind.

And then there’s the payoff: A freezer filled with delicious venison. Many times as I bite into a piece of fall-off-the-fork tenderloin steak, seared with onions in a cast-iron skillet, I think it was all worth it, all the hunting and dragging the deer out of the woods and butchering, just for this one meal.

It’s easy to tout the allure of savory meat and the thrill of the chase, but hunters know they have a bit of a PR problem with the killing part. As much as hunting magazines point to the strategy, the connection with the outdoors, the respect for the animal, all important parts of the hunting ethic, there’s still the cold fact that it all ties into firing a weapon at an animal, fatally wounding it. Outdoor magazines (not, you’ll notice, “killing animal magazines”) frequently use the euphemism “harvesting.” That’s possibly both for the sake of squeamish hunters and the odd nonhunter who will flip through the pages in a waiting room somewhere. These publications have strict rules for photos with trophies: No gaping wounds or large patches of blood-soaked hair, don’t let the tongue hang out of the mouth, pose respectfully (not, say, holding up the animal’s head by an ear or standing with a foot on its neck).

Some anti-hunters likely assume hunters like me are bloodthirsty—psychopaths with a legal outlet—who get a rush out of being powerful enough to end another creature’s life, and savage pleasure in the moment of death, like an overfed housecat that kills a bird just for the fun of it.

I’m not persuaded that cats aren’t psychopaths, but I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt and say instead they are like human hunters, with built-in instincts handed down over the millennia from predatory ancestors, both creatures getting satisfaction in gathering their own meat despite a plethora of store-bought options.

With both the butchering of farmyard animals and hunting, the killing is the central act, but it is not the point. It’s an unfortunate side effect of the reality that you can’t eat an animal unless it’s dead. It’s the final event in an adventure and personal challenge in the outdoors.

I see the wisdom in the rural practice of no-fuss butchering. Farmers will tell you the chicken’s friends aren’t going to particularly miss it. I don’t think it’s reflecting at the last moment on the choices it made in life, or reflecting on what all that fighting over the pecking order had been about, after all.

Or, maybe I was a young human tragically desensitized to the horror of slaughter, grown up to be an adult still warped enough to kill things. Why can’t we all just go to a grocery store like normal, well-adjusted humans and get our meat there?

Our ancestors knew much more than we do how central death is to life, how common and how everyday it is. They did not love death, but they lived with it. The farther we get from death, the more horrible and mysterious it seems.

Some theorists argue that meat, and the fire to cook it, are what enabled us to develop our large brains. Brains capable of knowing good and evil and feeling regret at the killing necessary to provide us with meat.

That healthy unease pushes all of us to draw moral lines. For something as drastic as killing, we don’t want those lines to be fuzzy. But the deeply uncomfortable fact is that those guidelines we hew to are not always logical or objective. One culture adores dogs; another eats them. It’s difficult to make a consistent case for why it’s alright to kill a flounder but not a koala. My parents firmly instructed me: Don’t kill songbirds. But why is a mourning dove a game animal and not a robin?

As an adult, I remain in the Mennonite faith, believing that I am to love everyone and answer violence with peace. I am also still a hunter, although I have sworn off butchering my own chickens for reasons of laziness.

Slaughterhouse workers kill repeatedly until they are numb to it; much of the rest of the populace grows up picking the savory morsels from the ribs while pretending they never belonged to a living animal.

I’m pushing my way through the thickets somewhere in between.

*

Learn more about Andrew on the Contributors’ page.

Vote for the overall winner of the 2026 Best in Rural Writing Contest! Read “The Escapee’s Lover” and “God, Guns, and Baseball,” and vote below one of the entries.

(Photo: Daniel/flickr.com/ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

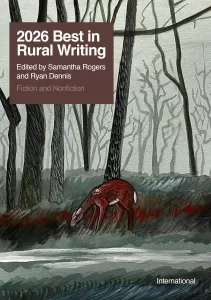

This carefully curated collection brings together outstanding essays and short stories that delve into the landscapes, lives, and voices of rural spaces around the world.

Coming soon!

- On Killing by Andrew Sharp - November 27, 2025