“I know what Winnie the Pooh would say,” Jasmine tells me.

She is driving with one arm hanging out the truck window. I can hear her thin metal bracelets jangling as we bounce along the dirt road at her family’s weekend farm. The smell of Mississippi clay and the carpet of pine needles drift through the open windows, and whenever the truck drops into a deep rut, the sharp tip of one of the springs in the worn seat pokes me in the butt like some gesture accompanying Jaz’s glibness.

“Come on, Jaz, I’m being serious,” I say, grabbing hold of the handle above the door as we go over a series of particularly bad ruts.

“Nothing is more serious than Winnie the Pooh, Macon.”

I keep my sigh to myself. I’d suspected I’d have to go through this kind of ribbing first. My cousin is like that: strong as the horses she loves, but skittish around any shiny emotion you flash in front of her.

“Pooh Bear would say, ‘I always get to where I am going by walking away from where I have been.’”

I puff my cheeks out in frustration. Jaz turns the steering wheel hard and takes a grassy turn-off toward the field where the horses are pastured during the week when the family isn’t here. My shoulder bangs against the door.

It’s a sign of my desperation that I’m asking Jaz what I can to do about my Nicole problem. I wouldn’t normally ask my cousin for advice. We aren’t that close. We sometimes see one another in the high school hallways where we wave or stop to say a few words, but with the three-year age difference, we really only talk when my family makes one of its infrequent visits to my aunt’s weekend house in Mississippi.

There is another reason I’m asking Jaz for help despite the fact that she is inclined to treat everything like a joke at first. She is—as my friends like to remind me whenever we see her around —a stone-cold fox who, according to the grape vine, has lots more experience than me. I figure it takes one fox to know another, and Jasmine might be able to fathom the way my girlfriend’s mind works better than I can.

If she is still my girlfriend when I get back to town.

Jaz’s honey-colored hair has come loose from her pony-tail in all the jouncing. She blows the strands from her face with a comical blast, like she knows she is being watched, which she often is. She’s got rodeo queen beauty: clear skin, a thousand-watt smile, and deep dimples that hint at secret pleasures.

She doesn’t seem to care much for her beauty, but she is well-aware of its effect on the boys around her. At least it seems that way. She isn’t above practicing some flirting on my friends, using my relation to her as an excuse to stop in the halls to test out a bright, half-teasing smile. And, sure, we know she isn’t really interested in us and is after the attention of the seniors, the way she jokes and hugs her binders to her chest to obscure the view that everyone is trying to get, but the truth is we don’t mind that she is using us as props to get to the older boys. We are glad of the attention.

Still, because we knew that we were just a means to something else, it was hard not to feel spiteful pleasure when a senior boy came up behind her one day, imitated her pose and added a hair toss for good measure. We admired the way he exposed her, put her in her place. It’s easy to feel weak through the knees around a girl like Jaz or Nicole, easy to feel betrayed by our bodies when the erections happen, unbidden and revealing. That senior’s imperviousness to Jasmine’s beauty and blithe maneuvers, the way he made light of them even, it made the rest of us feel that some kind of balance had been restored in the world, though when she turned to see what we were grinning at and the two of them locked gazes, we got the feeling that something beyond our reckoning had happened. Seeing the look pass between them made me feel the irritable frustration of a toddler trying and failing to reach something good on a counter. But it was also that knowing look that made me think that Jaz could help me with my Nicole problem.

Word in the hallways is that Nicole is about to drop me for Simon Lapere, two years older and two months away from having his driver’s license in hand. Doesn’t hurt that he is the placekicker for the football team, either. I’d felt Nic’s attention on me loosening over the past few weeks, and I’d begged my parents not to make me go to the country this weekend, worried that it would be just enough space for Simon to slip into the gap between Nic and me.

The idea of losing her is killing me, even though some part of me suspects it’s a done deal already. I haven’t admitted that to my cousin. Not in that way. Instead, I’d asked her how to keep Nicole. So far, I’ve only been quoted the philosophy of a fictional bear.

Jaz slows the truck as we bounce up the slight incline to the paddock fence.

“Get the gate, would you, please?” she says.

Impatiently, I jump out, unlatch the aluminum gate and walk it backwards so Jaz can drive in. She edges the truck through the gate and I swing it closed behind, careful not to slice my palm by sliding it along the sharp top slat as I had once before when I was a kid. Just the first of many seemingly harmless things I now recognize have dangerous tricks to them.

I climb back into the cab and Jaz eases us over the uneven terrain of the paddock. I brace myself against the dash and wait for the ground to even out. Even as an inexperienced rider, I am looking forward to having my butt in a saddle instead of on this beat-up truck’s seat.

After a few minutes, we pull up to another fenced-off field. The horses, Nantucket and Sasha, are several hundred yards out on the horizon, silhouetted against the white morning sky. They turn their long faces at the sound of the engine. Nantucket tests the air, then returns to pulling at the grass at his feet. Sasha shakes her mane like some music video model as she walks toward us. Nantucket follows slowly, nose to the ground as he comes.

Jaz shuts the engine off, opens her door and stands up on the running board. She sticks her index fingers in her mouth and gives a loud whistle. Out in the field, Nantucket raises his head and whinnies. He trots toward us.

While Jaz waits for the horses at the fence, she takes the generous sides of her long denim skirt and pulls each up to thread through the belt at her waist so that the fabric won’t flap and spook the horses. The result is that she looks like she is wearing some weird apron. I admire her precaution, but I have to do my best not to think of her as a girl when she wheels and her white calves and lower thighs are exposed.

Jaz goes around to the back of the truck and drops the gate. I climb out while she hops up onto the flatbed and hefts one of the saddles in it. “Here,” she says, handing it over the side to me. I slide my arms under it while Jaz jumps down and leans in to slide the other saddle to the edge of the flatbed. She lifts it out and we carry them to the fence where the horses are now waiting. She lifts her saddle and balances it on the top rung. I do the same. Nantucket moves down the rail to me and I scratch his forehead while Jaz goes back for the other gear. The horse plucks at my sleeve with his lips, nostrils flaring.

“I don’t have anything for you,” I tell him, showing him my hands. Insulted that I’ve come without an offering, he nudges me hard with his head. I grab onto the fence rail and refuse to be moved, knowing that the disappointed horse is testing my mettle. A couple of years ago, one of the horses used its flank to push me into the side of the barn, then turned its rear to me and kicked. I managed to dodge that deliberately-aimed kick, but the intention had made an impression. Horses are thinking animals with agendas of their own. The notion that thin aluminum fences can keep them in has always seemed foolish to me. I find myself thinking that the horses must be complicit in staying where they were.

“Here,” Jaz says, coming up behind me. She hands me the saddle padding. With the two bridles in her hand, she opens the gate and slips inside the paddock, closing the gate behind her. She puts her shoulder into Nantucket’s chest and leans into him to back him away from the fence. The horse moves grudgingly, and Jaz ducks under his neck to get to Sasha.

Jaz lays the bridles over the fence and takes hold of Sasha’s halter with her left hand, patting the horse hard on the neck. Little puffs of dust rise from the horse’s coat with each slap.

“Hello, gorgeous.” Jasmine lays her face against the horse’s cheek. “Shall we go for a ride?” She pets the animal’s neck for a moment, looking her in the eye, and then she takes a bridle from the fence and begins to gently scratch Sasha’s forehead to get her to lower her head.

“So,” Jaz says, returning to my subject. She sticks her thumb into the horse’s mouth to get her to open for the bit. “Nicole, huh?”

Nantucket is edging sideways, trying to mash Jaz between him and Sasha. I take hold of his halter and pull his head in the other direction while Jaz fits the bit into Sasha’s mouth and begins to work the horse’s ears through the crown.

“Don’t make fun of me.”

“Not me,” Jaz promises with a quick smile. She glances over her shoulder at me, and I can see the twinkle in her eyes. “Serious business.”

I hesitate, but really I don’t have anyone else I can ask about something like this. “I can’t tell if her flirting with him is serious or not,” I say. “Like, is she just trying to make me jealous by doing it?”

Jaz checks the bit and wraps Sasha’s reins around the top rail. She begins adjusting the buckles of the bit around Sasha’s face. The horse tongues the metal rod in her mouth. Unhooking the halter, Jaz hands it to me over the fence. I give her the saddle pad in return. She tosses the pad over the horse’s back and runs her hand over Sasha’s withers, adjusting the pad to sit high on them.

“Does she talk about the other guy a lot?” Jaz throws her shoulder against Nantucket’s flank as the horse leans closer to Sasha again. “Back away, Nan!” The horse snorts in acknowledgement, but doesn’t move. I take his halter again and pull him further down the fence.

I shake my head. “Not so much. Like, a normal amount.”

“What’s a normal amount?” Jaz asks, swinging the saddle up onto Sasha’s back. Sasha shifts her weight to three feet, balancing the front edge of her fourth hoof on the ground.

I shrug. “Like a normal amount for the placekicker on the football team?”

“What does she talk about?” Jaz reaches under the belly of the horse to grab the girth strap and latigo.

I shrug again. “Nothing. Stuff. She heard him talking about a movie we should go see. She likes a stupid t-shirt she saw him wearing. Just stuff.”

Jaz doesn’t respond. She takes a step down the length of the horse and reaches under the belly for the rear cinch.

“Sometimes it feels like she’s comparing us,” I admit. “Sometimes it feels like she’s trying to give me a message.”

Finishing with Sasha’s saddling, she ducks under Nantucket’s neck to stand on his left side. “Hand me Nan’s bridle, would you?” Jaz says.

I step up onto the bottom rail and lean forward over the fence to hand it to her.

She takes it from me. “What kind of message?” she asks, even though we both know. Even though my saying it out loud would make it true.

Past the horses and out across the field, the grass is drying out and the mild autumn sunshine of the late morning makes the edges of everything sharp and brittle-looking. There is something imminently expectant about an autumn field with an open horizon. The earth seems to go on and then the sky does. Too many movies make me always expect to see a band of heroic riders rise up on the horizon trotting toward me. This horizon stays empty. I turn the collar of my jean jacket up.

Jaz comes over to the fence, crosses her arms along the rail and waits, looking at me intently. Behind her, Nantucket stamps once, impatiently.

“She’s not the only girl out there, you know,” Jasmine says matter-of-factly.

What I want to tell my cousin is how I can’t stop looking at the curve of Nicole’s insole as her sandal dangles from her painted toes. About the cold tug in my testicles when I see Nicole’s rear end jiggling as she runs laps in P.E. About the hours I’ve lost dreaming about the shadowy space between the cups of her push-up bra, and how my blood whooshes through me like a flash flood boring through a slot canyon when I see her sucking on a strand of her hair while she takes her tests.

“I don’t want another girl. I want her,” I say.

Jaz pretends to be interested in separating the bracelets on her wrist. “But that’s the only part that’s up to you,” she says, all flippancy aside. “The other part isn’t.” Jaz turns away as if there is nothing further to say and tosses the second saddle pad up on Nantucket’s withers.

“Any preference?” she asks, swinging the saddle up on the Nantucket’s back. The horse huffs dramatically as Jaz begins cinching up. She gives Nan a quick jab to the side with a closed fist. “Quit holding your breath, stupid horse.” The horse exhales with the punch and Jaz pulls the latigo tight, threading it through the D-ring and back down to the cinch ring again.

“Well, yeah,” I say. “I’d prefer she really liked me.”

Jasmine presses her forehead against the saddle as if she is trying to hide the fact that I am too stupid to live. “I meant the horses,” she says.

“Oh.”

My cousin flips the stirrup down and turns to look at me, one hand on her hip, so capable, so blasé about my heartbreak. And then I’m mad. Really mad. Nicole makes me feel suddenly stupid and embarrassed like this, too. I think about the salacious, unkind things I’ve heard said about my cousin in the school hallways, think about how my friends told me the same kind of things about Nicole before we started dating.

“I’ll take Sasha,” I say, opening the gate and stepping inside.

“Leave it open,” Jasmine tells me. “We’ll ride them in that paddock. There were too many gopher holes in this one last time. Hop up and I’ll adjust your stirrups.”

In her tone, I think I hear a jab about boys’ inadequacy, and I feel off-balance the same way I did in the hallway before that senior righted things. I grab hold of the horn and cantle and put my foot into my cousin’s cupped hands for a boost. She counts to three and lifts me smoothly. I throw a leg over the saddle and the horse dips under me, adjusting to the new weight.

“Heels down,” Jaz reminds me, slapping my calf harder than maybe she has to. I do what she tells me, putting my weight onto my toes and lifting myself slightly on the stirrup. She begins to lengthen the stirrup. I lean forward to stroke the horse’s neck to hide my awkwardness at not being able to adjust it for myself. When the stirrup is buckled, Jaz moves around the back of the horse to the other side, trailing a hand on Sasha’s flank so the horse knows she is behind her.

When she finishes, she turns around and grabs the sides of Nantucket’s saddle, slipping a foot into the stirrup and lifting herself up onto the horse in one fluent movement. She lands in the saddle as if she were made of air. Other than the horse rolling his eyes backward, Nan gives no sign he’s been mounted. Jaz takes a second to arrange her skirt over her thighs.

With a sharp clicking sound, Jasmine pulls her reins hard right to turn the horse away from the fence and circle around to the gate next to me. “Pull straight back,” she directs as she leads Nantucket through the gate. I pull on the reins and Sasha backs away from the fence. When I relax the reins, she follows Nan through the gate. She brushes the gate post, trying to scrape me off like a burr.

“Quit it,” I scold, giving her a quick flick of the reins against the neck. She tosses her head and I hear her chew at her bit. Jaz has gone on ahead and I kick Sasha into a trot to catch up. She drops into a walk next to the other horse. We ride along the fence line toward the uncleared land on the other side of the field.

My cousin sits easily in the saddle, her lower back doing a languorous sashay along with her horse’s hips. She holds the reins in a loose fist that rests on the saddle horn. Easy, confident. I’m envious that she doesn’t have to think about what to do.

Jaz clicks her tongue again and urges Nantucket into a trot. Sasha follows her lead. I bounce ungracefully, trying to keep my seat.

“So?” I call, not wanting the subject to be closed. “What do I do about Nicole?”

The soil beneath us is hard from the lack of rain over the past several weeks, and my question comes out in an awkward little stutter as the horse’s feet connect with the ungiving ground. We are drawing closer to the trees. Jaz turns Nantucket back toward the open field.

“Nothing,” she says. “Move on. You’ll get over it.”

Not liking this answer, I cluck at Sasha and pull harder on my left rein than I should. She tosses her head and trots sideways before turning her nose to follow Nantucket. I try raising myself a little to get my butt out of the saddle, but the awkward gait keeps jolting me out of my stand, which just makes me angrier, and suddenly I want to tell my cousin what they say about her in the hallways. I want to hurt her.

Instead, I turn my face to the empty field we’ve just left. When I look back, Jaz has kicked Nan into a canter. The horse has fallen immediately into a beautiful hobby-horse movement with Jaz swaying back and forth in her saddle like water washing against a jetty.

I kick Sasha’s sides with my heels, but she doesn’t change her gait. I kick again, harder, two taps, and shift my weight forward in my saddle, urging her to catch up. She lunges forward, does a weird little prance, and falls again into the trot, knocking me off-balance over the saddle horn. Cursing, I grab the pommel to hold myself in place.

Up ahead, Jaz has kicked Nantucket into a gallop and has reached the middle of the field already. She leans into the run with heels pressed down hard and calves tight against the horse’s sides. Determined not to be left behind, I kick hard against Sasha’s flank and flap the reins against her neck at the same time.

The horse bolts forward. If not for the saddle horn, I would have surely tumbled backwards off her. Use your legs, I tell myself, but Sasha has gone into a full run and I am off-balance now, just trying to hold on as she races after Nantucket. Up ahead, Jaz has reined her horse back into a canter as they approach the far edge of the field, and is doing a slow loop back round toward us.

If I had I been sitting properly, I might have noticed right away that the saddle was slipping off the back of the horse, but because I am just trying to find my seat again, it is only when I realize that Sasha’s shoulder is in front of my nose instead of below it that I understand what is happening. I clench my legs in a panic and grab onto the saddle horn with both hands. I feel the saddle slipping further, am aware of the beautiful long line of the horse’s neck as she stretches forward into a gallop. Then the saddle slips fully sideways and I panic at the sight of the mare’s running legs so close to my face.

Across the field, I am aware of Jasmine spurring Nan into a gallop toward me. She yells and leans hard over her racing horse’s neck, but the sound of Sasha’s hooves striking the ground is thunderous and unrelenting now that I am only a few feet away from the ground. Tiny bits of sod strike me in the face as the horse kicks them up.

More from the centrifugal force than anything else I know that my horse is veering hard to the left, but that observation focuses into a sharp point when I realize that Sasha is heading for the open gate of the pasture. I fasten on two calculations immediately: the width of the gate and the width of me on the horse. The gate is plenty wide enough for a horse to pass through, but is way too narrow for a horse with a person riding sideways to pass through. The world contracts to the space between the approaching gate posts, Sasha’s pounding hooves, and the saddle horn growing slick between my fingers.

I experience a sick lurch that has nothing to do with the gait of the horse. I see how it will go: the gate post decapitating me as Sasha runs through, my headless body slamming back against her side, blood spattering over the horse’s fetlocks and belly, and then dragging behind as she slows down. If I let go and my foot doesn’t clear the stirrup, I will be dragged. My mind does a fast version of this death, too. It isn’t any less gory. I know enough people who ride horses to know that falling from a horse, even if you don’t get trampled or dragged, isn’t likely to end well for the bones in your body. I wonder briefly if Nic would care.

From across the field, I hear a voice screaming, “Let go, Macon! Let go!” I know it has to be Jasmine’s, but I’ve never heard my cousin’s voice as commanding as this. As if trying to outrun Jasmine’s order, Sasha puts on a burst of speed toward the gate. In the end, it is the suspicion that the horse is trying to kill me that loosens my fingers. I spend one last moment trying to ascertain whether my foot is clear of the stirrups, and then I let go.

Then I am a body in motion, an object in the grasp of gravity. Sound ceases and I am suspended in white space. Suspended in elided time. Then I am not. I thud against the ground, the smell of the hard dirt filling my nose as I roll.

The pounding of Sasha’s hooves become tiny receding thuds transmitted through the hard ground into my body. I turn over to lie on my back and face the white sky, throwing an arm over my eyes to hide the tears. Nicole is gone. I feel her going like the spring seeping that will soften the ground beneath me when the season turns. I wait for sound to re-enter the world and, with it, my cousin riding hard for me from the horizon.

*

Learn more about Elizabeth on the Contributors’ page.

(Photo: John/flickr.com/ CC BY 2.0)

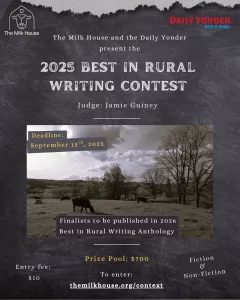

$500 first prize, $200 runner-up. $10 entry fee. Finalists will be published in the 2026 Best in Rural Writing print anthology.

Accepting fiction and nonfiction under 7,000 words. To enter, click here.

Deadline: September 15th, 2025

- A Body In Motion by Elizabeth Rosen - June 26, 2025