My father didn’t teach me how to drive a tractor, because, I suppose, he assumed that I knew. As a child I had sat in his lap, turning the wheel of the 3010, which had power steering and power brakes. Later, I moved to the tractor’s fenders, watching as he used the clutch, the brake, and the throttle. The hours gauge no longer worked, but the long handle on the right, I knew, engaged the power take-off.

I was eleven, maybe, and he wanted me to rake with the B, our smallest tractor.

–I…ah…, I said.

–Get on.

He nodded at the John Deere.

I climbed up and sat in the seat. I knew what to do. I had sat with him on it or stood beside him countless times, but I had never driven the tractor alone. I knew enough to pick the plates off the brakes, snap back the clutch, and tap the accelerator before I pressed the starter.

When the B came to life, the cap on the exhaust stack clacked. I sat. The possibility of flipping the tractor backward stopped me. I’d been warned.

Bent over the rake, a steel-wheeled John Deere, my father was busy with the grease gun.

I stared at the steering wheel. It was huge.

Then he appeared beside me, reaching for the stick, shoving it into first gear.

–Now, he said.

I pushed in the clutch.

–Slow! he said.

I eased the handle forward. The tractor lurched ahead and died.

–Jesus Christ, he shouted, climbing onto the axle, looming over me, I said, ‘slow’!

–All right, all right!

I sat still.

–Well, start it.

–Okay, okay.

The tractor started popping. I steered it around the rake, pulled the clutch, and braked.

My father stepped off the hitch bar.

–Now, back it up.

He lifted the rake’s tongue.

–Slow now, he said.

After shifting gears, I gently pushed the clutch forward. The tractor rolled back.

–Whoa!

He jumped aside as the hitch hit the rake, which rolled to a stop four or five feet away.

–Easy, he said, holding up the tongue. Let ‘er roll.

I backed the tractor up again, this time disengaging the clutch and letting the B go. I looked behind to see when the tongue and the hitch bar would align. Ready with the pin, my father dropped it through the hole and stepped away. I braked.

–I want you to rake the Flat, he said.

Ah, okay, I said. I took a breath.

He stepped onto the tongue.

–I’ll get you started.

I steered the B down the driveway, toward the Flat, the rake rattling behind, its tines tossing stones.

–Slow, he said, you’re shakin’ the shit out of it.

I pulled back the throttle and touched the brakes.

While I waited, he opened and closed both gates. In the field, he set the height of the reel, tested it, and adjusted it again.

–When you come ‘round, he said, slapping the left tractor tire, keep this wheel on the edge. And watch the corners.

And so I learned to rake, steering clockwise, rolling rows, round and round, moving closer to the heart of the field.

***

My father was a thin man, strong but not powerful, unlike many neighbor men, who were broad-shouldered and brawny. Never in good health when I knew him, he should have worked at something else, but as far as I know he never sought anything to do other than farm. He endured, despite an enlarged heart, which may have been due to myocarditis, an inflammation of a heart wall. After his heart enlarged, he was never at full strength and probably never felt well again. All I knew was that he went to bed early.

He smoked Lucky Strikes, which didn’t help his heart, and his heart failed him more than once. He usually worked wearing a faded ball cap, blue khakis, and a tucked-in T-shirt that had a pocket for his Luckies.

To dry, hay had to be turned. I was too small to help in the late ‘60s, but I followed my father and my half-brothers Bobby and Jack as they turned hay with pitchforks in the Piece-next-to-Turlip, a meadow of ten acres or more. The work took all day, more than one day, and rain meant ruin. As they flipped mown grass, they passed on, bringing up more brightness, which the sun dulled as the day wore toward dark. After Bobby and Jack complained loud enough and long enough, my father, a last holdout, bought a tedder, which scattered the green.

In 1962, the year he married, my father bought a John Deere 3010, the maker’s first diesel tractor, and the farm’s main power for the next thirty years. Before ‘62, a John Deere A and two draft horses powered the place. We owned a black Percheron and borrowed another from the Turlips. When our horse died in the pig barn, my father used a chainsaw to cut the door wide enough to pull the body out to drag to the woods. The last farmer around to give up horses, he had to find a new tongue so he could pull the rake with the B.

During haying seasons, he kept a pitchfork on the 3010. He’d slide a tine into a hole in the tractor’s perforated step and drop the handle onto the axle. At odd times he would stop baling and use the pitchfork to collect hay. Gathering stray handfuls made no sense when he had a field to bale and rain threatened.

Returning with an empty wagon, Bobby rolled the B up beside him.

–What’re you doin’? he said, throwing his hands at the sky. It’s gonna rain, for Chrissake!

–Ah, my father said, waving him off.

He raked the fork once more across the stubble. After tossing what he had gathered into the path of the baler, he replaced the pitchfork, climbed onto the tractor, and hit the accelerator.

Laughing in disbelief and shaking his head, Bobby drove on, unhooked the wagon, and waited, watchful.

When I saw my father walking the edges of a field with a pitchfork while the baler rocked, pulling in nothing, I thought he was keeping a clean field. When I learned later about the dry years of the early 60s, though, I imagined his anxiety at losing hay, any hay. With the pitchfork, he wasn’t getting all he could, he was making sure he had enough.

***

When Ann was two and I was four, my father ran her over with the 3010. This happened just before Labor Day 1967.

–Don’t you go near that field, my mother said, washing dishes at the kitchen sink.

I took a soup spoon from a drawer.

–I want you and your sister to play here next to the house, she said, where I can see you.

The screen door slapped shut behind me. Ann and I took blue buckets from the back porch and sat in a dirt patch near the house.

–C’mon, I said. Let’s go someplace else.

–Mommy said no.

–It’s okay, I said.

I took her arm, and we walked across the yard, slipped past the yellow flowers at the end of the stonewall, and sat in the driveway where we played among the loose cobbles.

The tractor, baler, and wagon banged downhill from the barn, black smoke streaming from the stack of the 3010. Bobby, just turned fifteen, rode the wagon. He had been living at the farm only a year and in a few days would start tenth grade at the high school in Forest City.

My father swung the tractor to the right and then back to the left to bring the baler in line with the second windrow. He engaged the power-takeoff, and the baler, a John Deere 24T, clanked to life and began taking up hay. On his left—his blind side—the tractor rolled in the road. As it drew closer to us, I heard the baler shoving hay into its chamber, but I didn’t tie the sound to us.

Ann and I dug in the dirt, dropping stones into pails, pushing and pulling each other. The tractor roared nearer, the baler jousting, its forks frantically pulling hay to the plunger, which rammed it back to the knotters. First cutting, the hay was heavy, so the windrow was big and the baler could barely take it in. Dust floated from the augur.

My father kept his eye on the baler’s pickup, adjusted the tractor’s path, and tapped the throttle. With the noise, he couldn’t hear shouts from the wagon or see Bobby waving and jumping into the road. The noise grew tremendous, and the tractor wheel loomed, casting shadow, close enough to touch. I yanked Ann’s arm, but she didn’t come far enough and the wheel snapped her leg.

She passed out. Dropping at her side, Bobby cradled her in his arms. His face drained of color, my father took her up and ran with her across the yard toward the car. My mother appeared, screaming. They laid her in the back seat, got in, and tore off to St. Joe’s Hospital in Carbondale.

The work went on, no matter the trouble. Bobby milked the cows that night, and they baled the hay the next day. As he watched Ann hobble in a cast for a month or more, my father likely replayed the scene, wondering why he didn’t see us, his playing children, imperiled.

***

My father died on the last day of haying in 2003, July 26. We had finished unloading the last wagon as the sun set and were in the kitchen eating hamburgers, happy it was over, so late in the summer. He had been mowing the yard while we were at the barn and when he left the table to lie on the couch in the next room, no one thought much of it. I heard him moaning and went to check on him. He looked at me with wide eyes, tried to say something, but couldn’t get the words out. Jack had followed me.

–Mom! he shouted.

She ran in, calling, Bill! Bill!

The rest crowded into the living room.

–Call an ambulance!

He sat up, and looked at us. Vomit darkened his green T-shirt.

–How do you feel?

–All right.

He lay back.

My mother shook him.

–Bill! Bill!

She got no response.

I called an ambulance. It took over half an hour to arrive.

The crew checked him.

–Goddamn, he said, as they slid a needle into his arm.

He hated needles and had an outsized fear of them. My mother said he let his teeth rot rather than submit to Novocain.

He groaned and didn’t move and they did CPR. They checked him again, rolled him into a blanket, and lifted him onto a gurney. It was dark now. Inside the ambulance, under a dim light, they did CPR again, more, maybe, to keep our hopes alive.

We jumped into cars and followed the ambulance to Wayne Memorial, in Honesdale. While we sat in the waiting room, my brother Danny called for help to do the milking, but neighbors were already at the barn.

A doctor appeared.

–Mrs. Conlogue?

As my mother approached him, he said, Your husband has died.

–No!

They had wrapped him in white and rolled the gurney into a small room. The space looked so clinical and bare, unlike anything that my father knew but closer to what I imagine that he feared most about hospitals.

The funeral mass was at St. Cecelia’s, a little country church at Hill Top, above Whites Valley, on the road to Honesdale. Most often we went to services at St. James, in Pleasant Mount, because they started later, at 10:30, which gave us time to finish morning chores. The mass at St. Cecelia’s started at 8:00. For my father’s mass, the church was full. When Father Albert invited people to speak, I should have, but I couldn’t. I had no words.

We stood outside with the coffin as a bagpiper played “Danny Boy.” My father was buried behind the church, among generations of family stones. These days, no one sings at St. Cecelia’s, and though the church still stands, a huge rock announcing its name sits square in the center of the walk, blocking the way.

*

Learn more about Bill on the Contributors’ page.

Learn more about Bill on the Contributors’ page.

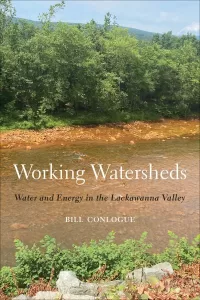

Bill’s latest book, Working Watersheds: Water and Energy in the Lackawanna Valley, was published by Temple University Press in 2024 and is available here.

(Photo: Justin Meissen/flickr.com/ CC BY 2.0)

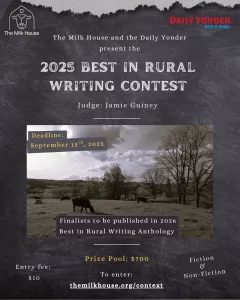

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is now underway!

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is now underway!

$500 first prize, $200 runner-up. $10 entry fee. Finalists will be published in the 2026 Best in Rural Writing print anthology.

Accepting fiction and nonfiction under 7,000 words. To enter, click here.

Deadline: September 15th, 2025

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is sponsored by The Daily Yonder. The Daily Yonder offers news, analysis and stories from Rural America, free for readers to enjoy. Visit dailyyonder.com to get more great rural stories, or sign up to their newsletter to receive rural reporting directly in your inbox. Alternatively, you can listen and subscribe to their podcast, Rural Remix, wherever you get your podcasts.

- Haying seasons by Bill Conlogue - June 10, 2025