Graveyards are memory places. Rural graveyards, in particular, with their shades of grey and green. There is a mossy feel to them, soft and damp. They shift by seasons, from hopeful green to birdsong green, then dappled green to inky green. Graveyards glisten. They hold weather. The evidence in their disrepair and flourishing, the hardness softening, the green taking over. Every Irish country graveyard has a sense of it having just rained or being about to. As if the memories there need frequent watering. Nature doing our work for us.

When I was small, I watched a television programme that invited me – and every other child too young for school – into a place of discovery. Come with me through the magic door, it said. I cannot enter a graveyard without that line shivering through me. The threshold of a graveyard requires a slowing down, a suspension of the daily world.

Graveyard gates creak, no matter how new. As if wherever and however such things are made, whether factory or forge – it seems the kind of thing I might have seen through the magic door but have long since forgotten – the gates for graveyards are made on a bockety belt, where the tongues and grooves and metallic bits and bobs never quite align. Reminding us that nothing is flawless, not even the person now gone, who, too, was once gloriously and imperfectly alive. The gate calls us to ourselves, reminds us where we are. That this is no ordinary gate. No side-of-the-house gate. No kissing gate at the start of a coastal walk. No walled kitchen garden gate. No theme park entry gate. No country house museum gate. No high-latched playground gate. No childproof gate at the bottom of your stairs. There is nothing childproof here. Beyond the gate, the creak says, our daily nonsenses cannot pass. Be respectful of that or stay outside.

Inside the gate, country graveyards have understandings. Not rules. Not exactly customs, either, or rituals. Not quite. Observances is the closest I can come to the mix of individual and community markers. That gets us alongside the truth of it. Nobody sticks to the path. In death, as in life, we rarely see our loved ones in a straight line. Instead, we zig-zag to them. We wander. We absorb the quiet. We ready ourselves. Visual displays of love abound – huge headstones, fresh flowers, benches, trinkets, but there is a guilty awareness that these are for the living. ‘You can’t take it with you,’ the saying goes, yet there we are in the graveyard, pressing our offerings into the ground as if foisting uneaten cake into the reluctant hands of a departing visitor and insisting they take it.

Country graveyards hum. They have their own frequency. The space is at its most quietly magical when birds are the loudest voices there. This is nature-hush, not church-hush, and so it is, despite everything it contains and represents, an entirely living quiet. In the ditches, things rustle and scurry about their business. What is a graveyard to a mouse, I wonder? Or death or mourning or tears, for that matter? Their lives are long, or seem so, to them. All small animals live in a slow-motion world.

Perhaps that is why, when visiting graveyards as a child, time stretched, slow as milk to boil, creating a restlessness that manifested itself in wishing a speedier end to the call-and-response of the endless rosary. If we looked, I wonder, would we find a single 80s child who didn’t fantasise about shaving a Hail Mary or two off their decade and getting away with it? That was possible only in graveyards, where the rosary beads – carried on the bus all the way to Knock to be blessed and too precious now to risk an outing – were replaced by fingers. Maybe that lazy river of time is why trees in graveyards seem always to have been there since time immemorial. Bent double under the weight of all the symbolism thrust upon them. The yew tree, famously, has to represent both death and resurrection and so be all things to all people, but even the other trees seem to shy away from standing upright. It doesn’t seem appropriate to reach for the sun, they say. We understand their reluctance. Graveyards bow our heads, our backs, too, although we are not trees. Our memories will not last centuries.

Graveyards are a space of universal, private assumption. There, you can cry in peace and be certain that everyone will leave you to it, not out of ignorance or neglect but in perfect understanding that, here, the mutable boundaries are between the living and the dead, not between strangers. Everybody’s heart will clench in solidarity and nobody will intrude. They are the most private of public spaces.

Yet it is also true that they reflect society. In towns, a grave in the churchyard is often reward for a lifetime of service to the institution of the church. I have stood in those graveyards and wondered at the logic. Is the idea that, come Judgement Day, God intends to poke his head out the sacristy door and whisper-shout only to those within hearing distance? Like a mother calling the children in after dark. A targeted summoning. In a medieval graveyard in Kilkenny, a local man explained that gravestone inscriptions had little use in less literate times. Instead, the shape of the stone denoted the family name, while its height told their social status. Their literal standing, inscribed in the landscape for all time. I marvelled aloud at their ingenuity – the man was lovely, it was either match his enthusiasm or, perish the thought, appear rude – while thinking with horror that a person could work their whole life and yet be eternally reduced to their family name and position. Modern headstones are more egalitarian and not just because of literacy – they reflect the movement of people away from where they were reared, the freedom that comes with finding your own path, your own place.

It is more than a decade since we were told that our two-month-old daughter would shortly die. As blow-ins, we were faced with the question of whether to bury Ali where we lived or take her back to where I grew up. The debate was short: where we lived was where she lived. Under other circumstances, she would have known my homeplace well, but her illness meant she had never spent a night there and I couldn’t leave her permanently in a place that would be strange to her. While I sang You Are My Sunshine to her at home, my husband was taken on a tour of the local graveyards by a neighbour who knew the value of practical kindness. I found it, he told me when he got home, and when he showed me, I knew he was right. It was the most glorious evening. The height of Irish summer is never the heat in the sun but how long it stays, stretching its pink fingers out towards us, like the von Trapp children singing lower and lower to delay their bedtime. He recognised the graveyard; I recognised the plot. In the corner, beside the wall and the wildflowers. Tucked in. The memories and love I leave behind are yours to keep is what we inscribed for her a few short months later and we do our best to guard those memories, to take them out and look at them, to polish them and share them with whoever will listen.

Because they are memory places, graveyards are haunted places too. How could they be otherwise? Haunted not by ghosts but by the memories of all we got wrong. Cross words, angry sighs, ungrateful thoughts. Things said and regretted. Things unsaid and regretted. More than once it has crossed my mind whether, given the choice, I would opt to know the date of my death, that I might be sure to have words and thoughts in order beforehand. On balance, I think I would regret knowing and be annoyed with myself for every lapse, spoiling the duration. I already know where I will end up – another tiny strangeness in being predeceased by your child is that you choose the stone that will eventually bear your own name. Even as an inveterate planner, I didn’t see that one coming.

Country graveyards hold a collective memory, perhaps because of the long oral tradition of prayers said aloud. I rarely hear people saying the rosary in the graveyard now. That is not a judgement – as an ex-Catholic, I haven’t said it myself for many years, although others will have their own reasons. Perhaps there is less coming together now, fewer voices rising in collective joy or misery. I wonder if, given time, the observances of rural graveyards will go the way of the ceilidh houses.

I wonder, too, what our graveyards have done with our collective grief at all the loss this past year. Perhaps we will get to these mossy places and find that while their ranks have quietly swollen in our absence, the rain has been pulling double duty: murmuring to the stones, softening hard new edges, hastening time. Nature doing our work for us, again.

In our daily lives, we are bound up in our bodies, attached to them to varying extents and extremes, sometimes patting them fondly, sometimes pinching them meanly. Yet in graveyards, our living bodies are oddly immaterial. We are pure memory. I think of the Japanese with their forest-bathing and wonder if we will need some graveyard bathing when this confined living is over. Rather than a connection of our physical selves with the earth, our graveyard bathing will leave the body behind entirely. Making of ourselves only spirit and air. An immersion in memory. In all that we have loved and lost.

Before I leave the graveyard, I touch my fingers to my lips and then to the rose carved on her stone. I think of Wendell Berry’s Canticle, ‘A creed and a grave never did equal the life of anything.’

You are very fragile, the creak in the graveyard gate reminds me as I leave. Foolish and fragile. But you are also full of memories and so you are never really alone.

![]()

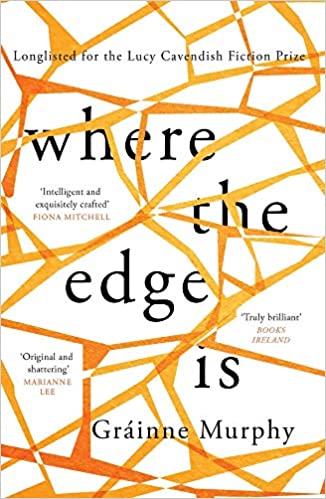

Gráinne Murphey’s novel Where the Edge Is was published by Legends Press and is available here.

Gráinne Murphey’s novel Where the Edge Is was published by Legends Press and is available here.

Find out more about Gráinne on our Contributors’ Page.

- Time Immemorial, by Gráinne Murphy - April 15, 2021