I remember the first time I heard about Facebook. A girl in my college class told me that it was “kind of neat” and that I should check it out. She described it to me: you create an online profile that says you like all sorts of eclectic bands and try to put up only pictures that make you look good. You can post anything, but mostly about what you cooked for dinner or what made you annoyed that day. You try to get as many “likes” as possible, because that makes you feel good.

I thought, that’s stupid. That will never catch on.

Fifteen years later, Facebook is so big that it is trying to bring out its own currency. Some pundits—including, reportedly, the US government—are starting to get nervous that Facebook may one day become large enough to be more powerful than actual governments.

It turns out I was wrong. Facebook did catch on.

Most people are willing to admit that technology is a double-edged sword: We’re gaining some sort of convenience, but often lose some other essential part of the human experience. (I appreciate how fast I can look up a restaurant on my Motorola, but worry when I see people unable to walk on the street without a phone in front of them.) Regardless, the thing is, most of us are unwilling to go back in time and live without the devices and gadgets that we’ve become accustomed to. In the same way, I don’t like what social media may be doing to people’s attention span and how they get their information, but I know it’s here to stay.

Although I could never imagine my father in the parlor with a selfie stick recording the morning milking to upload on YouTube, it was obvious that it wouldn’t be long until there were farmers who did. Needless to say, the Millennials in agriculture have it covered by now. Anyone so inclined can gorge themselves on tacky farming-related music videos, anti-vegan rants, endless clips of someone playing trombone to a herd of cows, and plenty of good-looking women driving combines. In Ireland, there is even a custom silage outfit called The Grassmen that have their own Youtube channel and sell merchandise for all the rural teens to wear.

Farming and social media are well acquainted by now.

The 1920s and 1930s saw a boom in the farm novel in North America. Everyone was writing about farming—even people who never passed by a cow or a field in their life—because it was the hot topic. There were more rural readers back then, and even those in the city wanted to read about the lifestyle that was different to their own. Since then, however, novels about farming have practically disappeared. There are fewer farmers, and fewer people to write about agriculture. The result is that there are less ways for those outside of the industry to learn about it, as well as opportunities for farmers to get to see their lived experience reflected back to them. The same can be said for films, with the portrayal of farming becoming increasingly scarce and inaccurate.

It seems, to some extent, that social platforms have been able to fill that gap concerning the presence of farming in media. Some YouTubers have become extremely popular (and wealthy) by chronicling everyday farming chores, suggesting that there is still a curiosity of what happens in a barn. I’ve stopped becoming surprised when a tweet showing a picture of cattle in a pasture gets several hundred likes. Social media, when all the cat memes and epic fail videos are put aside, has allowed some farmers to find a voice again and connect directly to consumers.

Ultimately, I’ve come to realize that the more I complain about social media the more curmudgeonly I sound. And it might be true: if you can’t beat them you should probably join them instead. Therefore, I spent this last summer making a video introducing The Milk House column.

I knew nothing about using a smartphone to record video or the software I needed to put it all together. In the end it was a lot of B roll of my father looking annoyed into the camera and asking me again why I’m recording him, and me telling my sister to make her kids look cute. Also, there’s plenty of shots of my girlfriend telling me to go away and do something with my life.

If nothing else, it was a handy way to chronicle the summer. I got footage of the goat that recently passed away at an unthinkable old age, as well as a notorious barn cat that later succumbed to an attack by some sort of wild animal. In this way, they get to be immortalized. Mostly, though, for whatever good it does in introducing The Milk House column, it did show me the value in getting to share something about myself with a greater audience. Sometimes, it’s nice to be seen.

So, I might take it to the next level. Coming up on my YouTube channel: rapping cats insult vegans while making silage. Subscribe now.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman, Farm and Livestock Directory, and Sheep Canada Magazine.

*

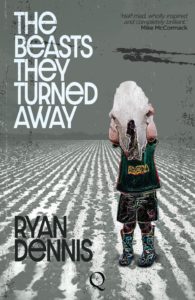

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.