They gave us white handkerchiefs and asked us to wear them over our faces for the purpose of anonymity. We were led to an idyllic fairground setting with a plank bandstand, square bales for seats, and a wooden wagon in the middle. It took a moment for the subtleties of the scene to emerge: women in burlap skirts and white sacks over their faces, ritualistic deer antlers hung from the top of a gazebo, a maypole with a horse’s head on the spire, and a blank-faced man leading a pigmy goat. The speakers began repeating a soliloquy from a woman describing going to a small town as a young girl and seeing a dead man strung from a lamp post, pondering what would cause the village to behave like this. After it was over, faceless actors came onto the stage to perform a cult-like rhythmic dance heavy with stomping and knee-slapping. Then we were ushered into the great silos that loomed above us.

I was visiting a friend in Buffalo, NY and my second night there he took me to a “site-specific artistic performance” in Silo City, an area by the Eerie Canal. Silo City received its name from the colossal grain elevators built there in the first decade of the 1900s. Positioning on the canal turned Buffalo into an economic powerhouse in the first half of the 20th century. Construction occurred quickly and with cutting edge technology of the time. Grain milling, storage and transport built the city and drove its development. The silos themselves were emblems of America’s industrial rise. They were even credited to be the inspiration of certain German architecture, exemplifying the essence of pure functionality and size.

They heyday of Buffalo, however, is unfortunately over. The opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959 and the advancement of other shipping industries eventually outdated the Eerie Canal. In rust belt fashion, the city soon declined economically, and then socially. The municipality’s unemployment rate is typically 3% higher than the national average. Public schools have a dropout rate of almost 50%. Even the city’s NFL team hasn’t been in the playoffs in 15 years (when this column was originally written). A character in a recent movie once said that to kill yourself in Buffalo is redundant. The behemoth silos themselves stand as towering, empty emblems of the better days gone.

In the mid-90s our farm converted from a 100-cow tiestall operation to a 200-cow freestall facility. One of the vestigial parts of the barn left over from the earlier days was the feed room and the harvester silos next to it. The feed room reminds me of my childhood, of watching my father running the auger and chatting away with Lenny, the harvester repairman, that was there whenever something broke. Farming was better then, at least for my family. We enjoyed the tiestalls more, and the days when 100 cows were plenty. Now the feed room is dilapidated, and the auger hangs motionless under a layer of dust. The whitewash has chipped away from the walls and litters the ground. It still smells like cornmeal and distillers, although what is left inside the machines has been repetitively mined by beetles. Whenever I’m in the barn and have a few minutes to pass I go into the feed room. Often, because it’s my occupation anyway, I bring pen and paper and write about farming.

The artistic presentation in Silo City was called “They Kill Things.” It was a disjointed and impressionistic story of two travelers entering a secluded, perplexing town as it prepared for its harvest festival with dubious rituals. The themes dealt with the origins of violence and the dichotomy of beauty and aggression sometimes inherent in religion. We were taken inside the silos to various sections that held installations of light and sound, as well as actors carrying out scenes or choreographed dance. At one point they lined us up while shirtless, bearded men strode up and down the row sparking their scythes on the concrete. Another time they dragged a corpse through the building and then hung it on a pulley outside while a choir sang below it. One room had a nurse gently massaging and singing to a scarecrow until another bearded man stormed in and hit it in the face with a sledgehammer. This was all accented by the smell old grain dust, which added to the strange mix of feelings, especially for a farmer’s son.

I loved it. Having an appreciation for both the arts and the bizarre, I came away with an experience that I’ll never have again, nor able to fitfully describe. In truth, I would have paid the admission just to go inside the silos, but it was the silos themselves that made the performance. Being a “site-specific spectacle,” as advertised on the theatre company’s website, it all started with the gothic grain elevators and created a concept based on the image they projection.

Old Agriculture and Avant Garde Art seem like an odd juxtaposition, which is perhaps why it worked so well. In fact, the show is just one of the ways the community is trying to bring life back into Silo City. A climbing wall was built on the side of one of the elevators and various readings and literary events are now being held there. Other art installations and movie nights occur in Silo City, as well as a flea market once a month in the summer season. My friend tells me that the city of Buffalo is on the rise again. Part of the reason, and perhaps the events at Silo City are emblematic of that, is finding ways to integrate the derelict spaces of its past glories. It doesn’t seem that Buffalo is concerned with recontextualizing the giant grain elevators so much as finding a way to incorporate the past into the presence. Nostalgia is easy, and perhaps even has its place, but that isn’t happening on the canal. The silos could have been figurative museum pieces, left as relics and nothing more, but instead people are finding ways to engage with them again—even in the unlikely manners of conceptual art and weekend recreation. It’s a way of recognizing what the city of Buffalo was in a manner that assimilates it into what it is now.

When I sit in the feed room it is with the ghosts of the past. It’s still strange to see such elaborate and once central equipment fade under the cobwebs. The room has been used for the storage of old plow parts and pieces of machinery, and in that way still maintains some utility. I suspect it will have other purposes in the future. I’ll admit that I can’t help but to see it as an artifact of the way life and farming used to be, and nostalgia creeps in. Still, on my better days, it’s a space that encourages me to bring out the notebook and to be conscious of the things around me. I haven’t completely resolved my feelings of what farming used to be and what it looks like now, but perhaps as Silo City suggests, there’s room for both.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.

*

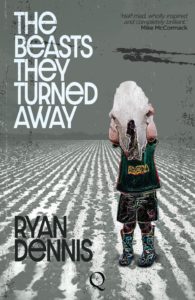

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now for pre-order here.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.