This was written a year ago, at the beginning of the coronavirus. Strange, funny, and discouraging how long ago that seems now.

*

I sit on the couch and stare at the fat gray squirrels waddling along the electric lines. I pick up an imaginary shotgun and point it at them. I wince when I pull the trigger, but the squirrels keep chasing each other around the walnut tree. It appears that I missed again.

I was first relieved, and then alarmed, at how easy it was to get back into the United States. My girlfriend and I caught one of the last flights out of Bolivia and made it through Panama next, where most other schedules were already cancelled. She’s Italian, which isn’t in vogue these days when it comes to international travel. Every time that she suggested that it would be fine since she hasn’t been in Europe in months I would point out that it was the US we were trying to get into. I’m an American citizen and each time they barely let me in.

Instead, here are the things that didn’t happen: There were no temperature checks, no pressure to self-quarantine, no asking if we felt ill in the last few days or had been around people who felt ill, and no pamphlet with a number to call if we felt sick. The immigration officer smiled, stamped our passport, and welcomed us to the United States of America.

I leaned towards my girlfriend as we waited by the luggage belt. “Wasn’t that a bit too easy?”

Currently, we’re renting an AirBnB in Rochester, NY, the city where our last plane landed. More accurately, it’s in the suburbs of the city where we landed. It was only after I lived abroad that I realized that suburbs, more or less, are an American thing. Pleasant-looking homes spread equidistant on a quiet street with medium-sized lawns and at least one kitsch lawn ornament: There is no more predictable expression of middle class-ness than the American suburbs. In short, it’s disgusting.

Having just arrived in a developed country, it feels like everyone else has a headstart in negotiating life during a pandemic. Today I went for a walk and crossed paths with a man pushing a pink tricycle. I stepped into someone else’s lawn to give him a wide berth. In doing so, I didn’t know if I was suggesting that he was diseased, or if I was. We both kept our heads down as we passed, which seemed like splitting the difference. I could have turned around and told him that part of him was already dead because he lived in the suburbs, but I didn’t.

One characteristic of rural America that is different from other places is that you’re given a shotgun when you’re ten or eleven and allowed to hunt gray squirrels. It’s a thrill that age to be in the woods and feel dangerous and have a source of prey. Instead, seeing the complacent squirrels poking along the grass outside the window makes me feel nothing but banal.

My girlfriend and I went for a big grocery shop before officially starting the quarantine. These days we’re all told to stay six feet apart. We’re promised that if we do this we will flatten the curve. I wasn’t sure how that would look on the ground, but found that other shoppers waited patiently for their turn at the top of the aisles and stayed out of the way. We did the same for them, sometimes pretending to peruse selections of Fruit Roll-Ups or canned spaghetti that we had no interest in buying, just not to feel awkward.

I felt good about how we were all doing in regard to negotiating the public space, until I saw the arm that reached over my shoulders for a bag of oranges. I had been living among the notoriously-short South Americans for two months and in Ireland before that, so the sheer size of the man behind me was shocking. Seven feet, two meters, half a storey—it didn’t matter how you measured him.

If I was braver I would have said “Hey Big Man, six feet apart.” But I’m not. And he continued to roam the aisles untethered.

It makes me wonder if that’s how it will be when society entirely breaks down—the biggest man gets the toilet paper and the bread and the women of childbearing age. The rest of us will live on canned spaghetti. Or maybe I should say when it all falls apart, not if. My girlfriend asked me why there are places where Americans are standing in line to buy guns. She wonders what they think they’ll need them for.

I tell her not to worry. It’s just for the squirrels.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman and was translated into Irish on Tuairisc.ie.

*

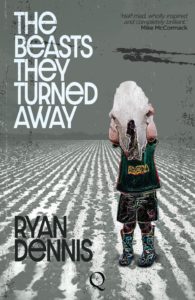

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.